The Good, The Bad and The Ugly of Equity Stripping

Although equity stripping can be effective (and sometimes the only) means to protect assets, it requires much skill to implement properly. Poorly designed programs are often either vulnerable to fraudulent transfer rulings, or are costly from a tax and/or economic perspective.

In addition to exploring the benefits of equity stripping, this chapter seeks to identify potential flaws in certain equity stripping programs, along with creative solutions that sidestep these problems.

Obviously, if a creditor obtains a lien on your asset, your assets could be jeopardized. At the same time, liens can be extremely useful. This is because a properly completed (a.k.a. ―perfected ) lien will, with very few exceptions, take precedence over all future liens as long as it is in effect. If all of a property’s equity is attached to existing liens, then all future liens placed on your property will essentially be worthless to their holders. This is because there is no equity left for the subsequent liens to attach to, which means if a junior lien holder (whose lien doesn’t).

Oftentimes, equity stripping is the only viable means of protecting an asset.

For example, financed property usually can’t be transferred into an LLC or other limited liability entity without technically triggering a loan agreement’s ―due-on-sale clause. If the clause is triggered, then the lending institution typically reserves the right to accelerate the loan, making the entire balance payable within 30 days. Failure to repay the entire loan may result in foreclosure on the property. Even though lenders usually choose not to accelerate the loan if a due-on-sale provision is triggered, I strongly recommend against playing with fire! To be safe, you could get the lender’s written permission to transfer property to an LLC or other entity. However, the Garn-St. Germain Act4 allows us to equity strip most properties without needing a lender’s permission to do so.

Another situation where equity stripping is desirable is when one is protecting their home. Under §121 of the Internal Revenue Code, a property that is a person’s home for two years in any five year period qualifies for an exemption on the gain if the property is sold. This exemption is $250,000 for an individual or $500,000 for a married couple. Although placing the home in a single member LLC (SMLLC) or other entity with ―disregarded entity tax status will preserve this exemption, placing the home in a family limited partnership (FLP), family LLC (FLLC), or corporation will not. Therefore, it may instead be more appropriate to strip the equity to the FLP or FLLC. Also, it is usually not a good idea to hold a strictly personal asset in a business entity. The reasons for this are more thoroughly examined in the chapter ―Asset Protection a Judge Will Respect.

Yet another major benefit of equity stripping is that it can be used to protect anything of value. For example, a gentleman once asked me if I could equity strip his race horse. I answered yes, you can even equity strip a horse! If a creditor then tried to seize the horse and sell it, an equity stripping program would ensure the creditor wouldn’t get a dime for doing so – all money would go to the senior lien holder, which happens to be an entity that’s friendly to the debtor. Thus, equity stripping can protect assets that are not only difficult or impossible to move offshore (such as real estate), but it can also protect assets that cannot easily be moved outside of a business and leased back (such as accounts receivable.)

Now that we understand the basics of how equity stripping works, let’s examine programs that are vulnerable to failing under court scrutiny (the Bad), programs with painful tax and economic consequences (the Ugly), and programs that have neither shortcoming (the Good.)

Cons of Equity Stripping

THE BAD

Bogus Friendly Liens

This act is found in 12 U.S.C. §1701j-3(d). An excerpt is as follows: ―With respect to a real property loan secured by a lien on residential real property containing less than five dwelling units, including a lien on the stock allocated to a dwelling unit in a cooperative housing corporation, or on a residential manufactured home, a lender may not exercise its option pursuant to a due-on-sale clause upon—

(1) the creation of a lien or other encumbrance subordinate to the lender’s security instrument which does not relate to a transfer of rights of occupancy in the property‖.

A disregarded entity is any entity that is ignored for tax purposes. Instead, all of the entity’s activities are treated as activities of its owner. Disregarded entities include grantor trusts, single member LLCs (SMLLCs), and Disregarded Entity Multi-Member LLCs (DEMMLLCs.)

By far the most commonly used of the flawed equity stripping strategies is the bogus lien. A bogus lien involves a friendly party (either a relative, LLC, Nevada corporation, or other entity) filing a lien against the target asset. The lien is ―bogus because the owner of the target asset receives nothing in exchange for granting the lien. In other words, there is no loan or bona fide obligation as a basis for the lien. Even if there is a basis for the lien, the lien may still be bogus if its basis is much less than the lien’s amount. Under the UFTA, a lien must be an amount that is of ―equivalent value‖ to the debt or obligation.

What’s worst, under the UFTA bogus liens fall in the category of fraud-in-fact, which is much easier to prove than constructive fraud. Consequently, although the bogus lien is easy to implement and maintain, it is also usually pretty easy to attack and eviscerate. Should a bogus lien occur shortly before a creditor threat arises, a knowledgeable attorney should have little problem convincing a judge to invalidate the lien. Nonetheless, despite the weakness inherent in bogus liens, the fact that they are not a widely known tool means they may offer limited asset protection if they are inconspicuously implemented far in advance of any creditor claims.

THE UGLY

After the Bad, we must examine the Ugly. Ugly programs usually work as far as asset protection is concerned, but they can be quite painful economically. Let’s examine these Ugly programs so that you can avoid potentially painful hidden costs and tax traps.

Tax Consequences of Certain Valid Friendly Liens

Not all friendly liens are bogus. If a friendly party gives you an actual loan that is equivalent in value to the lien; for example, and he is not an ―insider as defined in fraudulent transfer law, then the lien will probably survive a court’s scrutiny. However, there may still be problems with such a lien. First, you need to find a friendly person or business entity (which you may or may not have funded with your own cash) that is willing to loan you money on friendly terms.

My experience is that people generally have more wealth placed into hard assets than liquid assets. Therefore, you may find it difficult to scrape together enough personal wealth to equity strip your $500,000 home. Second, the interest payments that arise from equity stripping business assets may not be tax-deductible (especially if the equity stripping program also involves the purchase of a personal asset such as life insurance, discussed below), but they will almost certainly be considered taxable income to the lender. If you have a friend who loans you

See the UFTA §4(a)(2).

Although §4(a)(2) of the UFTA says that a transfer is fraudulent if no exchange of reasonably equivalent value is received in exchange for the transfer, it also stipulates that a fraud-in-fact transfer must also occur (1) during or shortly before a business transaction in which the remaining assets of the debtor were unreasonably small in relation to the business or transaction; or (2) the debtor intended to incur, or believed or reasonably should have believed that he would incur, debts beyond his ability to pay as they became due. If both of these criteria are not met, then a bogus lien will not automatically be considered a fraudulent transfer, although it may still be considered fraudulent if the creditor can prove the transfer occurred ―with actual intent to hinder, delay, or defraud any creditor of the debtor (see UFTA §4(a)(1).)

Under §1(7) of the UFTA, an insider is a relative, business partner (who has significant control or voting influence in the business), or a business entity that an individual has significant control over or voting stock in. Interestingly enough, a business partner who doesn’t control the business, and a business that the individual doesn’t control (at least directly) is not an insider under the UFTA.

If he owns money and he’s genuinely profiting from interest payments, then he shouldn’t mind paying the tax. However, if he intends to gift your interest payments back to you so that you aren’t losing money in the arrangement, then someone is going to have to foot the tax bill.

Finally, remember that if you receive a cash loan, you now need to protect the loan proceeds from creditors, and also make sure to structure the promissory note (a.k.a. loan agreement) so that the loan is not paid down gradually over time.

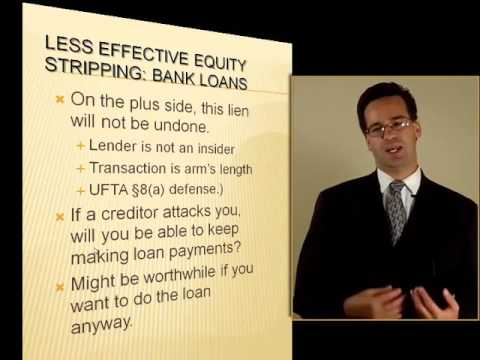

The strength of any lien held by a legitimate commercial lender is it’s practically impossible to invalidate. The weaknesses are everything else, especially from an economic standpoint. To illustrate the point, let’s look at the drawbacks of taking out a 2nd mortgage to equity strip a home. In this example, the home has a fair market value of $500,000 and an existing mortgage of $200,000. The problem with taking out a 2nd mortgage to equity strip is threefold. First, commercial lenders usually only loan up to about 80% of a property’s value9, leaving 20% of the equity exposed. Securing additional loans to completely encumber the property usually involve very high-interest rates (typically 15% or so.) Second, as the loan gets paid down, the property becomes less and less encumbered and therefore more equity becomes vulnerable. Third, the cost of making interest payments on the loan can be quite expensive.

For example, say you take out a $200,000 2nd mortgage on the property, to equity strip it to 80% of its value. If this was a 30-year loan repaid in monthly installments at 7% interest, you would pay $195,190.00 in interest before the loan was paid off. If you take out another loan for $100,000 in order to strip the property of all equity, you may pay 15% interest. Under the same repayment terms as before, the interest payments equal an additional $355,198.40.

Inflation notwithstanding, this is a very expensive means of asset protection! Of course, you could invest the loan proceeds in government bonds, annuities or life insurance, but you will still likely end up paying more than you would earn with these investments. Riskier investments (such as stocks) could provide a greater return, but you could also lose money and end up worse off than if you hadn’t invested the proceeds at all.

Even from a non-economic standpoint, there are still problems with commercial equity stripping. For example, mortgages are typically paid down over time, leaving more and more equity exposed to a creditor. Furthermore, if you find yourself under a creditor attack, you may very well lose the means to make loan payments. Therefore, if you don’t have cash set aside outside of a creditor’s reach, you may find yourself defaulting on your loan, resulting in foreclosure of the very property you were trying to protect! Although these last 2 problems may be overcome, other commercial equity stripping shortcomings may be difficult or even impossible to remedy.

Occasionally a commercial lender is willing to offer a home equity line of credit up to 125% of the property’s value; however, these loans are often difficult to qualify for unless the applicant has an extremely high credit score. The interest payment costs remain problematic.

The concept behind accounts receivable (A/R) premium financing for the purpose of asset protection is relatively simple. Essentially a business uses its A/R as collateral to obtain a loan, which is then used to purchase a life insurance product or annuity. Because many states protect such policies from creditors, the reasoning goes, the loan proceeds have been protected while also protecting (via equity stripping) the A/R. Furthermore, because the policy accrues interest, this helps offset the loan’s interest payments.

Equity stripping in such a manner has become a very popular asset protection technique. I need to make it clear that the biggest reason these programs are popular is not that they work (although the best programs do work.) Rather, these programs are popular because they are very lucrative for their promoters. For example, an asset protection planner convinces you to take out a loan for $100,000, using your A/R as collateral for the loan.

Equity stripping in such a manner has become a very popular asset protection technique. I need to make it clear that the biggest reason these programs are popular is not that they work (although the best programs do work.) Rather, these programs are popular because they are very lucrative for their promoters. For example, an asset protection planner convinces you to take out a loan for $100,000, using your A/R as collateral for the loan.

Then, he tells you to invest the money in a universal life insurance policy, because your state exempts these policies from the claims of creditors, and furthermore you could always borrow cash from the policy in the future if you needed to, right? Sounds like a great way to protect your A/R, right? Well, what the promoter didn’t tell you is he just made up to $55,000 from this arrangement, and although this program may very well protect your A/R from future creditors, A/R equity stripping through premium financing contains many traps and pitfalls, and most programs out there do not avoid these pitfalls.

Consider the following:

Contrary to what many believe, interest payments your company makes on a loan it took out to purchase an annuity or life insurance policy for you are often not tax deductible (you may or may not be able to overcome this problem if you work with a competent tax attorney.) Almost all loans secured by A/R are variable rate loans, whereas your life insurance product or annuity generally grows at a fixed rate, or in accordance with the stock market’s performance.

In other words, three months after you take out your loan, you may be unhappily surprised with rising interest rates on your loan, which makes your A/R financing program much more expensive than you thought it would be. Now you’re stuck between a rock and a hard place. That’s ugly! Although the policy you bought may be exempt in your state, if the company that sold you a policy operates in other states, then a judgment creditor could enter their judgment in a state where your policy is not exempt. Because the insurer operates in that state, and your policy is not exempt there, the creditor could seize your policy in the non-exempt state. Congratulations, you just lost your $100,000 policy, but you still have a $100,000 loan to pay off. Super Ugly!!!

Above all, remember this: a life insurance salesman can earn up to 55% commissions by selling you a life insurance policy. In other words, he makes up to $55,000 by selling you a $100,000 policy as part of an asset protection program. Do you think some of these insurance reps might be looking to fatten their pockets, rather than set up a plan that’s best for you? Do you see the conflict of interest here?

Now I must emphasize that equity stripping A/R through premium financing is not always a bad way to go; it is sometimes possible to overcome all A/R premium financing shortcomings if you use a planner that really knows what he’s doing (most don’t.) But, considering that many people who’ve done this type of equity stripping were afterward very

unhappy, make sure you’ve addressed all the potential traps and pitfalls before committing to such a program.

THE GOOD

Pros of Equity Stripping

Now we come to the Good ways to equity strip. I need to emphasize that even a Bad program may protect assets, and some Ugly programs can avoid their Ugliness (though most don’t.) The reason the following programs are Good is that they more easily sidestep equity stripping pitfalls. However, keep in mind that proper equity stripping requires much skill, and even a Good technique can turn Bad or Ugly if done incorrectly.

As we’ve seen, almost anytime a lien involves cash, there tend to be several pitfalls awaiting the unwary. However, a re-reading of the legal definition of the word ―lien‖ gives us valuable insight into how these traps may be avoided:

“lien” means a charge against or interest in a property to secure payment of a debt or performance of an obligation [emphasis is mine.]

Quite frankly, it amazes me that other asset protection planners fail to capitalize on the fact that liens are commonly used to secure obligations, and are every bit as valid as cash loans. Furthermore, it amazes me that other asset protection planners don’t realize a lien securing an obligation is superior in many ways to a lien securing a loan. For example:

It’s very easy to structure a security agreement so that the lien is not reduced or paid down until your obligation is completed in full. You can even structure the agreement so that the lien grows until the obligation is fulfilled. Your secured obligation almost certainly has absolutely no value to a creditor, whereas the cash proceeds of a loan always have lots of value to a creditor, meaning you’ll have to jump through more hoops to protect the loan proceeds.

If you’re in trouble with creditors, your liquid assets may be unavailable for loan payments, meaning you are protected if the property is in danger of foreclosure. However, since creditor troubles should not affect your ability to fulfill non-monetary obligations, (or rather we could arrange a monetary obligation with a ―friendly entity) foreclosure is not a problem.

You don’t have to worry about ―how am I going to get $625,000 to equity strip my $500,000 home? Cash loans are easy to quantify, making it very difficult to justify a large lien securing a small loan. However, certain obligations can be difficult to quantify, which gives us-See Title 11 USC §101(37). Note that this definition is in harmony with §1(8) of the UFTA.

More leeway when we are structuring an obligation to be of ―equivalent value to the cash value of a lien.

With the above in mind, let’s examine some ways in which a bona fide obligation may be used to place a valid lien on your property.

One of my favorite methods of equity stripping is via LLC capitalization, a method developed to rectify the shortcomings of other equity stripping programs. The concept goes like this: two people form a Limited Liability Company (LLC) in order to run a business (which could be some legitimate, yet easy-to-do activity such as investing in stocks and bonds). Under the LLC Acts of every state, each member (member being the LLC equivalent to partner) can obligate the other, per a written agreement, to contribute capital (assets) to the company so that it has the means to operate. One of the members contributes a smaller amount of assets up front to capitalize the company, in exchange for a small but significant ownership interest (usually 1-5%).

The other member promises to make a large capital contribution over time, in exchange for an upfront large interest in the company (95-99%). Because the first member contributed his capital up front, but the second one did not, the 1st member has a valid reason for making sure the 2nd member makes good on his promises. Therefore, the LLC places a lien on the second member’s property to ensure he fulfills his obligation to capitalize the LLC over time. As long as the LLC is not considered an insider under applicable fraudulent transfer law, and the obligation is valid, its fulfillment demonstrable, and it ―makes sense in a business context. A rock-solid lien has been created on the 2nd member’s property. Such an arrangement is illustrated in Figure 1, below.

FIGURE 1

Structuring a loan or obligation to be of equivalent value to a lien is a critical consideration under fraudulent transfer law. See UFTA §4(a)(2).

It’s important to note in this scenario that Member 2’s promised contribution could take many forms. It could be a promise to contribute cash, services, equipment, or other property. After the lien expires, the members could dissolve the LLC and typically all returns of capital will revert back to them tax-free. Furthermore, almost any type of asset could be equity stripped via this method, whether it be A/R, real estate, or personal property. Indeed, the flexibility of equity stripping via LLC capitalization is so great, that practically any type of asset could be protected, according to practically any terms that fit within the realm of normal business practice.

As a corporate officer of several companies, I am often tasked with reviewing various real estate lease agreements. Most of these agreements contain a lessor’s lien clause. These liens are not part of an intentional asset protection program; rather they are liens that arise in the normal course of business. As mentioned previously, a lien may be used to ensure someone meets an obligation. In this instance, the lessor wants to make sure that the lessee fulfills his lease, so oftentimes a UCC-1 financing statement (used to perfect a lien against non-titled property) is filed against the lessee’s accounts receivable, furniture, equipment, and other assets. Of course in this situation, the lessor is not trying to protect the lessee’s assets against other creditors, but that is exactly what he’s doing.

The best asset protection planners understand how liens are used in such everyday business arrangements, and they capitalize on such processes. Utilizing a standard business arrangement for asset protection is especially desirable because it appears that no intentional asset protection was done. Because normal business arrangements often use accounts receivable to secure a lease agreement, a lessor’s lien is an especially good way to protect this valuable asset.

The best type of lessor’s lien, of course, is one that is held by a company who is friendly towards the lessee, because we can then draft the lease and lien terms to best suit our needs. Often times I will take property in business, sell it to another business, and lease it back to the original business. This is called a ―lease-back arrangement, and has two benefits. First you protect one piece of property by putting it in a separate entity, and then you lease back the property to the original entity and put a lessor’s lien on a second asset. For example, an LLC could sell an office building to a 2nd LLC, lease the building back to the 1st LLC, and subsequently place a lessor’s lien on the 1st LLC’s accounts receivable.

As simple as the concept sounds, a lessor’s lien in this or similar circumstances still requires a high degree of skill to do correctly. The trick is to transfer the original asset into a separate entity in a manner that won’t be considered a fraudulent transfer, among other things. Also, one must structure each entity so that they’ll be respected as separate entities if challenged in court. For example, sometimes if one entity is being sued, and the managers of that entity also happen to manage the 2nd entity, both entities will be considered to be only one entity under the ―theory of interlocking directors.

This piercing of the veil of the 2nd LLC will not only avail the 1st LLC’s creditor of the 2nd LLC’s assets but also invalidate the reason for a lien on the company’s accounts receivable. Therefore if you wish to do a lessor’s lien between friendly companies, make sure you hire a skilled professional to assist you.

Despite the advantages of equity stripping via LLC capitalization and the lessor’s lien, these programs may not completely meet an individual’s needs. For example, if an individual wanted to protect their $500,000 free and clear home, they would have to promise a large capital contribution of either services or cash to the LLC. Honoring such an obligation might not be desirable. Furthermore, if the person who held the obligation manages the LLC, then the LLC that holds the lien would be considered an insider under fraudulent transfer law. Although this does not necessarily mean a fraudulent transfer has occurred, it may somewhat reduce the lien’s chance of survival if its validity was challenged. Fortunately, multi-stage equity stripping allows us to overcome these obstacles.

Multi-stage equity stripping is simply the process of placing two or more liens on a piece of property. If the target property is real estate (the most common equity-stripped asset), we most often have a client use the property to obtain an Equity Line of Credit (ELOC). The benefits of an ELOC are fourfold. First, although the lien is filed when the ELOC account is opened, one need not pay interest or other fees until the ELOC is actually used. Only under severe creditor duress does the ELOC even need to be exercised. Second, oftentimes homeowners wish to ―un-trap equity in their homes, so that they may invest the proceeds for profit.

Although the lien is placed on the asset when the ELOC account is obtained, the lien is dormant for practical purposes unless the line of credit is used. Once creditor threat arises, the ELOC should be fully utilized, with loan proceeds being transferred out of creditor reach. We often accomplish this by using ELOC proceeds to purchase an asset of equivalent value that is unavailable, undesirable, and possibly exempt under law from creditors, such as an offshore annuity from a major foreign insurance company.

Often those using an ELOC try to claim an income tax deduction on ELOC interest payments. Such individuals should be aware that the maximum ELOC balance towards which interest payments are deductible is $50,000 for a single individual or $100,000 for a married couple. See IRS publication 936 (2004) for more information. This publication may be accessed at http://www.irs.gov/publications/p936/ar02.html#d0e2069.

ideal means of doing this. Third, an ELOC can continuously strip a target property of 75% or so of its equity. Unlike a traditional mortgage, which will gradually be paid down, one can choose to only pay interest on the ELOC (or, if principal payments are required, then the repaid principle could be taken out again), thus ensuring, if necessary, that an increasing amount of equity will not be exposed to creditors. Furthermore, because much of the equity is stripped via an ELOC, it is easier to strip the remaining equity with an equity stripping via LLC capitalization program. Finally, even if a less than ideal (strength-wise) equity stripping via LLC capitalization program is used, from a creditor’s standpoint, the program will only attach to the least desirable equity.

This is because if a creditor forecloses on a debtor’s real property, the property will likely only sell for 60-80% of its fair market value. Because the ELOC typically covers this equity anyway, and the ELOC has virtually no chance of being undone by a court, the creditor has little incentive to challenge the 2nd lien. Despite this fact, we still wish to place the 2nd lien on the property, to cover its equity in case the property appreciates, or if in the future the owner decides to sell the property for fair market value while a junior judgment or other ―hostile‖ lien is encumbering the property.

Implementing the best program for your situation is not all we must know in order to protect assets via equity stripping. We must also know what to do if a judgment or other non-consensual lien, such as a federal tax lien, attaches to equity stripped property (hereinafter we’ll include all such liens when we use the term ―judgment lien). Although a judgment lien may not attach to any actual equity, if we ever sell the property, the lien may follow the sold property afterward. Since prior liens are usually paid-off at the point of sale, this means that these hostile liens could then be the first liens on the property once the buyer acquires it! Of course, this would be unacceptable to the buyer, as well as to any institution that might finance the purchase; so before selling this property, we must get rid of all hostile liens.

This is accomplished by having our friendly lien foreclose on the property. Foreclosure, of course, is only necessary when you want to sell equity-stripped property that has junior hostile liens on it. Often a favorable settlement is reached prior to this occurrence, and thus the hostile lien is removed and foreclosure is not necessary.

Before discussing foreclosures, we must warn that not all states treat foreclosures identically. Therefore, checking with a local attorney is a must before foreclosing. With that in mind, foreclosures typically happen one of two ways: by judicial foreclosure, or by a private party foreclosure. The type of foreclosure depends on the type of lien filed against the property. If the lien is a mortgage, then foreclosure occurs under court supervision. A deed of trust is foreclosed without court oversight. Obviously, a deed of trust is easier to foreclose, since it doesn’t involve the court, and therefore a deed of trust should be used as the lien document of choice whenever possible. Regardless, however, expect to pay $2,000 to 5,000 to for the entire foreclosure process.

The foreclosure process usually requires posting at least a couple public notices of such in a local newspaper or other publication, and it can take anywhere from three to six months from its inception before the actual auction occurs. The auction will typically be held by the deed trustee if the lien is a deed of trust, or a sheriff if the lien is a mortgage. When a foreclosure sale is held, the minimum bid is usually the amount of the lien that is being foreclosed.

The winning bidder must pay at least this amount, or more if he bid above the minimum. However, when the bidder acquires the property, it is still subject to senior liens. For example, if we have a $500,000 home with a $400,000 1st mortgage and a 2nd lien (which is our equity stripping program) on it for $250,000, and the 2nd lien forecloses, the bidder must pay at least $250,000 and he still pays on the $400,000 mortgage note after he acquires the property. Any liens junior to the foreclosing lien, however, are wiped out, and the buyer has no obligation to pay them.

Obviously, in our preceding example, the buyer would not be getting a good deal. He’d pay at least $250,000 for a $500,000 piece of property, but he’d still have to pay off the $400,000 1st mortgage. This begs the question ―what happens if no one bids at the auction, since doing so may not be a good deal? In this case, if there are no bidders, then the lien holder who foreclosed becomes the new owner of the property, which is still subject to senior liens but free of junior liens.

If this lien holder was an entity friendly to the property’s owner, it could then sell the property, and sale proceeds would flow into that LLC, thus remaining out of creditor reach. Careful planning would even allow us to restructure the entity so that the Internal Revenue Code §121 exemption14 on gain upon sale of a personal residence is allowed when the property is sold.

In summary, although equity stripping requires great skill to do correctly, creative and knowledgeable planners should have no problem finding an effective equity stripping method that meets their clients’ needs while minimizing the expense and effort involved in maintaining such a program.

Section 121 of the IRC allows one to sell a personal residence that has appreciated (up to $250,000 if the seller is single or $500,000 if married) without recognizing taxable gain upon sale. The seller must live in the personal residence at least two of the five years immediately preceding the sale in order to qualify for this exemption